to the gold shipments sent from the Victorian diggings to Melbourne. In 1854 the Victorian gold fields were the scene of what has been described-incorrectly-as Australia's only battle.

The miners had a number of grievances; licences were expensive, especially for miners whose claims were unproductive, and they were administered inefficiently and unfairly. Nor could the miners change this unsatisfactory arrangement, or leave mining to farm, for they could not vote and were unable to obtain land.

|

|

| 2

versions of the uniform of Gold Escort Trooper, 40th Regiment of

Foot, 1855 |

|

Upon its arrival in 1852 the 40th Foot formed a Gold Escort of 125 men in order to protect shipments of gold from the diggings to

Melbourne. The Gold Escort took no part in checking miners' licence s and searching for bushrangers. It was equipped and uniformed as the Honourable East India Company's Bombay Light Cavalry. Full dress uniform for rare

ceremonial parades consisted of the 40th's Albert shako and a French grey jacket with white piping and leather reinforced overalls.

(Above left) The escort's working dress comprised a loose-fitting red jacket, buff breeches (the 40th's facing colour was buff), long riding boots and black leather equipment. A black shako was worn with a white Havelock cover and neck cloth in

summer. (Above right). Images by Lindsay Cox |

In October 1854 an apparently corrupt verdict against the murderers of a miner at the Eureka Hotel roused the men on the hitherto quiet Ballarat diggings, west of Melbourne. The miners sought reform of the administration of the goldfields and political rights, establishing a reform league to press their case.

|

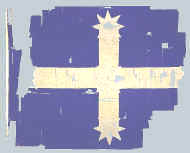

The Eureka

Flag is thought to have been designed by a Canadian gold miner by the

name of "Lieutenant" Or "Captain" Ross during the Eureka Stockade uprising

in Ballarat, Victoria, in 1854.

According to Frank Cayley's book Flag of Stars

the flag's five stars represent the Southern Cross and the white cross

joining the stars represents unity in defiance. |

| The

blue background is believed to represent the blue shirts worn by many of

the diggers, rather than represent the sky as is commonly thought.

The flag above is considered to be the "genuine

design" of the Eureka Flag (a number of variants seem to have

existed), as it is the design of the flag torn down at the stockade by

Police Constable John King on the morning of the miners' uprising -

Sunday, 3 December 1854. The torn and tattered remains of this flag is

kept at the Ballarat Fine Art Museum.

|

The original &

genuine Eureka Flag (1854)

wool and cotton

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery Collection.

|

|

The authorities reacted tactlessly to the diggers' modest demands. Governor Sir Charles Hotham despatched troops and later naval guns to Ballarat and the local civil police (Joes' or 'traps' as they were known) conducted aggravating licence hunts. Late in November a company of the 12th arrived in Ballarat in vans. The commander of the detachment allowed his party to be ambushed as they arrived. Vans were overturned, ammunition was stolen and a drummer was killed. The Mounted Police galloped to their rescue.

|

Tension increased on the diggings. On 30 November the goldfields commissioner provocatively ordered another licence search and troops and miners

skirmished among the claims.

The governor had described the diggings as 'a

network of rabbit burrows-for miles the holes adjoin each other; each is a

'

fortification'.

On I December about 1000 diggers swore to fight to defend their

rights and liberties, pledging their allegiance under the blue Eureka flag.

Companies of men were formed, pikes were manufactured and a stockade of

pit slabs was created on the Eureka claim on the main road to Melbourne west

of the town and the troops' camp. The miners' password was 'Vinegar Hill'.

The next day only some 500 men were left in the stockade. Others slipped away, realising the hopelessness of the contest.

By the evening of 2 December less than 200 diggers remained. Many were foreigners, some of whom had fought for liberty in the European revolutions of 1848.

About half were Irishmen, who identified the struggle against Britain with the miners' quarrel. A group of American diggers, the Independent Californian Rangers Revolver Brigade, manned outposts around the stockade.

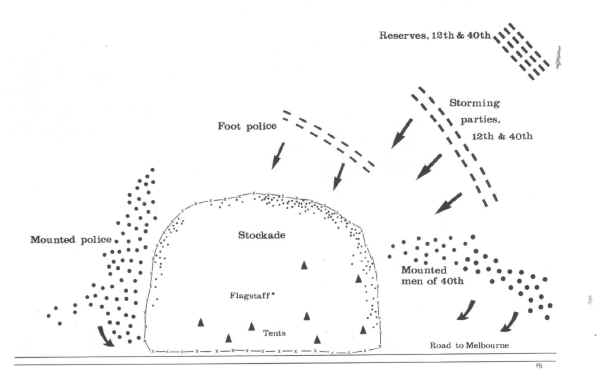

That night the troops, numbering two companies of the 12th and a company of the 40th, with 100 mounted troops and police marched from their camp toward the stockade.

In the half-light before dawn on 3 December the infantry assembled opposite the stockade while the mounted troops flanked it from north and south.

Only the miners' pickets saw the attackers. Both the government and the miners claimed that the other fired first.

It is likely that when the lines of infantry were 100 yards from the breastwork a few ragged shots met them.

The troops replied and wavered before moving forward at the encouragement of a bugler.

|

| Eureka miner, 1854. While the Eureka rebels had in Peter Lalor a

commander in chief they were by no means organised to resist the troops

sent against them. The diggers did not wear a 'uniform' of any sort, however,

the red and blue checked flannel shi rts worn by many miners and the corduroy or moleskin

trousers, stout boots and a "wide awake" or cabbage-tree hat gave the

insurgent diggers the appearance of military formation.

Many foreigners were present among the six companies which held the stockade,

though it was probably not intended to be defended but to act as a screen - their drilling. |

|

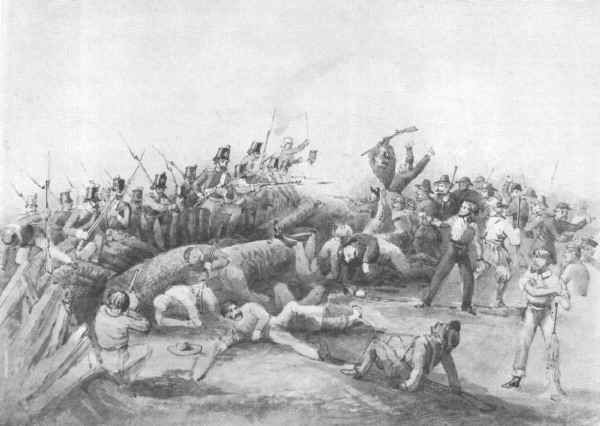

| The storming of the Eureka stockade; a vivid and reasonably accurate illustration by H.B. Henderson, who arrived at Eureka the morning after the battle. A member of the Independent Californian

Rangers Revolver Brigade can be seen at right, firing his revolver at the troops swarming over the breastwork. As the artist arrived on the scene after the attack, he has depicted the troops in the shakos in which they appeared later in the day (Mitchell Library). |

They swarmed over the breastwork, throwing the diggers, many of whom had just awoken, into confusion. American diggers armed with revolvers were notable in the brief hand-to-hand struggle inside the stockade. An official report of the action described them dashing up towards the soldiers to ensure a better aim, and thereby preventing the riflemen and other comrades from supporting them. Men armed with rough pikes stood their ground in the face of trained troops with Enfield rifles and

bayonets, but within ten minutes the Eureka flag had been torn down, tents were aflame and those diggers not dead, wounded or captured were fleeing the stockade.

|

| The Eureka stockade. The attack on the Eureka stockade, Ballarat, dawn December 1854. From the map by D.S. Huyghue in Walter Withers'

History of Ballarat. Details of the attack and even the location of the

stockade itself are subject to disagreement. |

In the attack, which Governor Hotham described as a 'well concerted and able movement', the troops suffered five killed (including Captain Wise of the 40th) and twelve wounded, while 34 diggers were killed or died of their wounds and 120 captured, some of whom were injured. The mounted police, many of whom were former convicts from Tasmania known as 'vandemonians'. behaved with particular brutality, but all but twelve of the captured diggers were released soon after the attack.

|

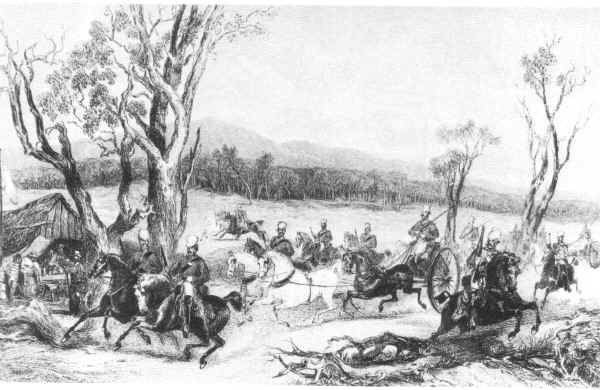

| Samuel Brees' engraving of the 40th's Gold Escort on the road from Bendigo to Melbourne shows the troopers on 'active service'.

They form advance rear and flank guard s for the caissons, riding in pairs. In contrast to their comrades still with the regiment these men sport moustaches (National Library of Australia). |

|

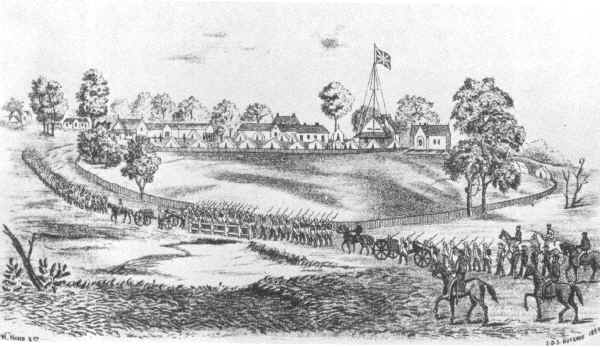

| The government camp at Ballarat, with troops and naval guns arriving from Melbourne, late 1854; a lithograph after

S.D.S. Huyghue (Australian War Memorial). |

Martial law was declared from 6 December but was lifted three days later. The gold field was pacified largely by the good sense of General Sir Robert Nickle, the Peninsular war veteran commanding the troops in Australia. Nickle moved among the

diggers' tents without an escort in the week after the battle and became liked and respected by the insurgents. The miners' grievances were substantially rectified in the following year, and all but one of the men tried for their part in the rebellion were acquitted. The Eureka stockade remains as one of the most evocative symbols of Australian resistance to official repression.

Social

Order Notice

Government Printers Melbourne

Collection: Ballarat Fine Art Gallery |

Down

with License Fee!

Collection: Ballarat Fine Art Gallery |

For the remainder of the decade the troops stationed around the six Australian colonies endured the routine of garrison duty familiar to most regiments of the mid-Victorian army. Both the Crimean War and the Indian mutiny were of great interest to the colonists. The former stimulated volunteer military units among the colonists, while the mutiny caused the 77th to embark for Bengal in April 1858 only seven months after its arrival in Sydney.

|

During the 1850s old soldiers, part of the Enrolled Pensioner Force, arrived to guard convicts in Western Australia.

The pensioners were a significant part

of the colony's population, comprising an eighth of its free inhabitants. The last pensioner was discharged in 1880.

<<< Hat badge of Local

Companies - Enrolled Pensioner Force (WA)

|

In the 1850s the first Royal Artillerymen to be permanently stationed in Australia arrived in Sydney, fifty years after the first of many requests for guns had been made. In Sydney the gunners manned batteries around the harbour and Fort Denison, a martello tower in the harbour with two 10 inch and twelve 32-pounder guns, while other gunners served the batteries defending Port Melbourne.

Sydney had been defended since the first months of settlement with guns in batteries at the mouth of the cove. Macquarie fortified

Bennelong Point by erecting a stone keep-named Fort Macquarie-in 1821. By the mid-1820s, though, these defences had fallen into disrepair. Several governors had expressed concern that their defences were inadequate: Darling protested in 1827 that Sydney was 'totally destitute of every military defence' , In 1835 Captain George Barney, a Royal Engineer officer trained in fortification, arrived-but worked mostly as a civil engineer.

Little was done to defend the colonial capitals until the 1850s: not until discovery of gold and the establishment of responsible government did the colonial middle class begin to fear for their prosperity. Imaginative governors, officials and pamphleteers considered their ports to be vulnerable

to the appearance of 'hostile cruisers', ready to threaten them with bombardment in return for their hard-won gold. Visions of French or Russian cruisers, or even of free-booting 'filibusters', appearing off the heads were to haunt the rulers of the Australian colonies for the next fifty years.

|