| "a Japanese force

landed near Gona on the north coast of Papua, with orders to reconnoitre

the feasibility of using a route over the mountains to launch an attack

on the major Allied base at Port Moresby, on the south coast. Within a

short time this force had been substantially reinforced to mount a

full-scale offensive, the intention being to support it with an

amphibious landing at the eastern tip of Papua – a plan which gave

rise to another major battle around Milne Bay in August-September.

Initially, the Japanese advance inland

made rapid progress against light Australian resistance. Opposing the

Japanese was "Maroubra Force", comprising the 300-strong

Papuan Infantry Battalion and an Australian militia unit, the 39th

Battalion Patrols clashed at Awala on 23 July before the defenders fell

back on Kokoda, which itself came under attack five days later. The

Australians were forced out during the early hours of the following

morning, following the death in action of the 39th's commander,

Lieutenant Colonel W. T. Owen. (His name is recorded on panel 68 of the

Roll of Honour).

On 8 August Owen's replacement, Major

Alan Cameron, returned at the head of 480 men to attempt to retake the

place. Outnumbered and short of ammunition, they were again forced to

relinquish control after two days of fighting and fell back along the

jungle track leading south up into the mountains, to the next native

village called Deniki. After beating off several Japanese attempts to

eject them from this position too, eventually on 14 August the 39th

Battalion and the Papuan Infantry began to fall back again, this time to

Isurava.

For nearly two weeks the Japanese did

not heavily press the Australians. During this time the 39th Battalion

was joined by another militia unit, the 53rd Battalion, and the

headquarters of the 30th Brigade under Brigadier Selwyn Porter. On 23

August part of the seasoned AIF 7th Division had also reached the

forward area. This was the 21st Brigade led by Brigadier Arnold Potts,

and comprised another two battalions (the 2/14th and 2/16th) numbering a

little more than 1000 men in total. Command of Maroubra Force now fell

to Potts.

|

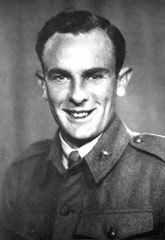

Private Bruce Kingsbury VC

2/14th Infantry Battalion

AWM 100112

|

When the Japanese resumed their

advance on 26 August – the same day that Japanese marines went ashore

at Milne Bay – Potts was forced to mount a desperate and difficult

fighting withdrawal aimed at denying ground and causing maximum delay to

the enemy. During the fourth consecutive day of fighting at Isurava,

Private Bruce Kingsbury led a gallant counter-attack against a breach in

the Australian perimeter which earned him the Victoria Cross - the first

won on Australian soil (which Papua then was). Sadly, this gallant

soldier fell to a sniper's bullet during his charge and his award was a

posthumous one. (He, too, is recorded on the Roll of Honour, on panel

38.)

Potts and his men fell back first to

Eora Creek on 30 August, then Templeton's Crossing on 2 September, and

Efogi three days later. As one writer has described it: "From 31

August to 15 September the Australians, against vastly superior numbers,

fought a decisive military game of cat and mouse along the track.

Company by company, platoon by platoon, section by section, they

defended until their comrades passed through their lines, broke off

contact sometimes 20 to 30 metres from the enemy and repeated the

procedure again and again down the track."

Throughout this fighting, Australian

resistance was increasing in strength and becoming better organised

while the Japanese were showing signs of feeling the strain of their own

lengthening supply line. Both sides, however, were beginning to suffer

the effects of reduced effectiveness caused by exhaustion and sickness

entailed by operating over such harsh terrain. Moreover, the Australian

build-up, while still relatively modest, proved impossible to sustain

via the only supply line stretching over the mountains, which depended

on native carriers to manhandle rations and ammunition forward, and to

evacuate the sick and wounded to the rear. The commander of 1st

Australian Corps at Port Moresby, Lieutenant General Sydney Rowell,

accordingly decided to withdraw the tired 39th Battalion on 5 September

to relieve the problem.

After another hard-fought stand at

Brigade Hill between 8 and 10 September, Potts handed over command to

Brigadier Porter, who decided on a further withdrawal to Ioribaiwa. Here

the Japanese attacked next day but made little progress. In fact, severe

fighting continued around Ioribaiwa for a week. But the Japanese advance

was losing impetus, while the Australian defence was gaining in strength

through the arrival of more units of the 7th Division. Command of the

forward area passed to Brigadier Ken Eather, leading the 25th Brigade,

AIF, on 14 September. In addition to its normal battalions (2/25th,

2/31st and 2/33rd), that brigade also had attached the 3rd Battalion and

the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion – a total of 2,500 combat troops.

It was to continue his defence from

the strongest available ground that Eather chose to withdraw to Imita

Ridge on 17 September. Although this was the last effective barrier

preventing a march on Port Moresby, the limits of the enemy advance had

actually already been reached by this stage. Supply lines had been

stretched beyond breaking point, leaving many Japanese troops starving

and unsupported, and other events were intervening – principally the

reverse suffered by Japanese forces fighting American marines at

Guadalacanal in the southern Solomon Islands. As early as 18 September

it had become clear to the Japanese commander at Rabaul, Lieutenant

General Hyakutake Harukichi, that the gamble he had taken with an

overland advance in Papua had failed. By then Guadalcanal was an area of

higher priority to which other effort had to be diverted.

After the local Japanese commander,

Major General Horii Tomitaro, received orders to establish a primary

defensive position around his landing bases on the north coast, he began

withdrawing on 24 September. The Australians were able to follow up the

retreating Japanese, reversing the path they had been forced to follow

during the enemy advance. It was a phase in the fighting which reached

its triumphant culmination on 2 November, with the re-occupation of

Kokoda.

From there Australian and American

forces pressed on northwards to seize Popondetta, which became the main

forward base for a long drawn out and costly campaign to eject the

Japanese from their coastal strongholds at Buna, Gona and Sanananda. But

that, as the saying goes, is another story.

The Kokoda Trail had taken a heavy

toll of the men on both sides who were engaged in the fighting. More

than 600 Australian lives had been lost, and over a thousand sustained

wounds in battle; perhaps as many as three times the number of combat

casualties had fallen ill during the campaign. Losses among the Japanese

had been equally severe, with somewhere around 75 per cent of the 6,000

troops engaged being accounted for as sick, wounded or killed. By the

time the last enemy bastions at the end of the overland route fell on 22

January 1943, the lives of more than 12,500 Japanese would be lost.

Professor David Horner, one of

Australia's leading historians of this campaign, has observed that:

It is ironic that many

of the reasons for this tragedy are similar to those that caused

suffering and death to the Australians (although not on the same scale).

Neither side appreciated the debilitating effect of terrain, vegetation,

heat, humidity, cold (at higher altitudes) and disease while operating

in the Owen Stanley Range.

As we reflect back after an interval

of 60 years, it would be easy to overlook both the dimension and

importance of these events. It is especially deserving of note that the

brunt of the initial fighting fell, on the Australian side, to

ill-equipped and poorly-trained young soldiers – many of them

18-year-olds who had never fired a rifle in anger – who were often

outnumbered perhaps five-to-one; moreover, their Japanese adversaries,

veterans of China, Guam and Rabaul, were equipped with heavy

machine-guns, mortars and mountain guns – weapons which the

Australians lacked. It is for this reason that the Kokoda Trail is

rightly remembered as a high point in Australian history. Along with

Milne Bay, the Kokoda campaign remains the most important ever fought by

Australians to ensure the direct security of Australia.

The campaign was also notable because

so much misunderstanding existed back in Australia at the time about

what was actually happening along the Trail. While the Australian

defenders were steadily falling back before the advancing Japanese,

their's was no abject retreat but a tenacious, uncompromising and

measured withdrawal – a fact which General Douglas MacArthur and his

senior officers failed to appreciate or acknowledge. Sackings of

commanders alleged to have failed to hold or reverse a situation which

was much more difficult than armchair strategists could possibly

realise, and slurs about men running like rabbits (made

by Tom Blamey, the Australian CinC), paid no regard to the

true magnitude of the performance and achievement of the troops on the

Trail.

These days, however, the name Kokoda

strikes a responsive chord with ordinary Australians, and it is

recognised and appreciated that the hardy men who fought so bravely

during the dark months of 1942 – especially those men whose names

appear on the walls behind me here – won a major victory, turning the

tide of Japanese successes to that time, and securing the Australian

homeland from the threat of sustained or serious attack. We remember

them all with respect and pride.

Partial extract of a speech by Dr

Chris Clark. Dr Clark has been Historian for Post-1945 Conflicts at the

Australian War Memorial since the beginning of 2001. |