|

|

|||

|

The 3rd Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) |

| Known as the battle of Passchendaele, the third battle of Ypres was the collective name given to campaign that lasted until November 1917 aimed at capturing the Gheluvelt Plateau in southern Belgium. The actions in which Australians took part were Menin Road, Polygon Wood, Broodseinde, Poelcappelle and Passchendaele. |

|

Chateau Wood, Ypres, October 1917 IWM E(Aus) 1220 |

"I died in hell. They called it Passchendaele". Siegfried Sassoon

| |

|

|

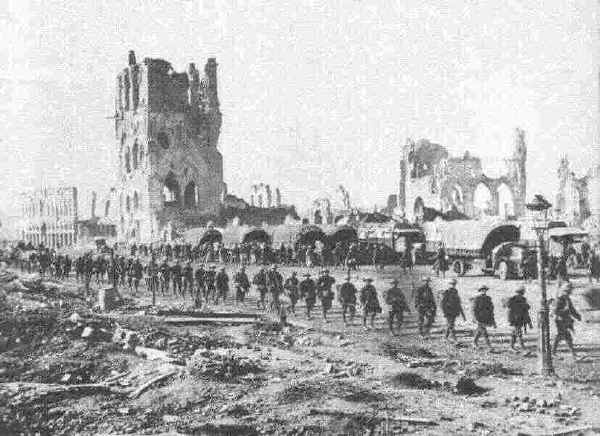

Australians moving through Ypres 25 Oct 1917 |

|

(The edited text of a paper given in France in November 1993. The original paper was illustrated by contemporary slide photographs and maps; this text is best read in conjunction with a map of the area.) by Geoffrey Miller © In 1915, at the second Battle of Ypres, the Germans used chlorine gas for the first time in warfare and succeeded in driving the British back to the town of Ypres. Here a bulge, or salient, was formed in their front line which left the town exposed on three sides to shellfire. The town was gradually destroyed, although of course it continued to be used as an important military centre for the Allied lines and all troops left for the front line through the Menin Gate. In 1917, the area of Flanders to the east of Ypres had great strategic importance because it was dominated by a German occupied ridge from the East to the South of Ypres. This was the only high ground in a flat, featureless plain and, if the British could only break out of the Ypres salient and take it, they could turn North and drive the Germans from the Belgian coast and capture the ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge from the enemy. The German position in Belgium would be outflanked and their industrial heartland in the Ruhr would be under threat.

U-boats were operating out of Zeebrugge with great success and the Admiralty was increasingly gloomy about what would happen in the English Channel if the Belgium ports were not closed to the enemy. Pressure had consequently been put on Field Marshal Haig to make an attack in Flanders. Haig's plan was to strike out of Ypres to the North and East and, in conjunction with a seaborne landing on the coast of Belgium at Nieuport, he would capture the high ground at Passchendaele which was the key to the whole area. This would allow the cavalry to be released in open country and sweep all before them to the coast. Haig, who had been trained as a cavalryman firmly believed that cavalry had a place in modern war; he was a very stubborn unimaginative man who completely disregarded the effects of barbed wire, machine guns, shells and fire from aircraft on the very vulnerable horses. An attack in Flanders would also hold down the German reserves and relieve the pressure on the French, who needed time to recover from the bloody shambles of Verdun that had caused the French army to mutiny.

Three main factors that should have been addressed prevented Haig's plans from being successful: these were the battlefield itself, the weather and the German defences. 1. The Battlefield The Ypres salient occupied a low lying, gently undulating pastureland, which had been reclaimed from marsh over the years by an elaborate drainage system. The water table was near the surface, even at the height of summer, and this reclaimed land was extremely vulnerable to shellfire that would destroy the drainage system and allow the land to flood. There was no layer of gravel and flooding would rapidly turn the whole battlefield into mud once the shelling started. The low ridge from Keppel to Passchendaele was shaped rather like a sickle with the handle at Messines and the blade sweeping round Ypres with Passchendaele at the tip and this ridge dominated the battle area. The Steenbeeck was one of a number of insignificant little streams that were to achieve great importance, after shelling and rain transformed them into an insurmountable barrier across the axis of the attack, because of the bog created by the shelling. Although Haig had been warned about this, he hoped that the breakthrough would be so swift that the land would not have time to bog. He seemed to be an incurable optimist who was quite incapable of learning from his recent experiences on the Somme!

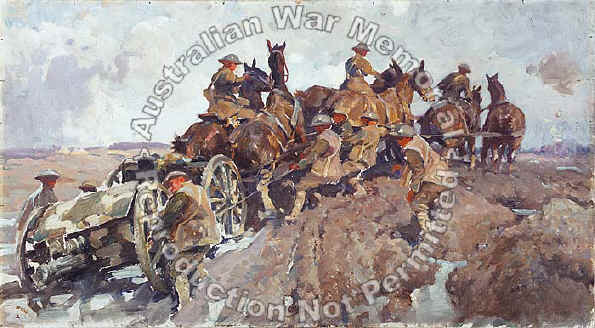

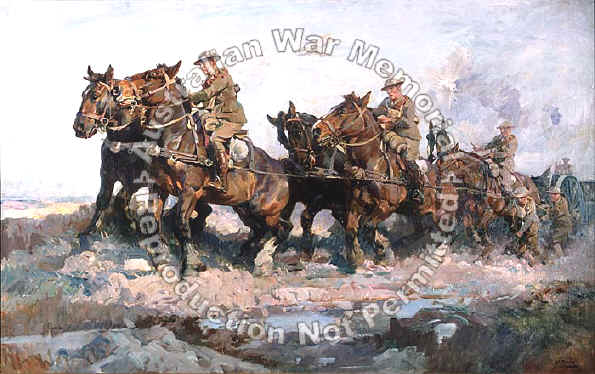

2. The weather Flanders was notorious for wet weather that usually started in the late autumn and the plan was for the attack to start in July, after the successful but limited Battle of Messines in June. It was known that July and August were the most unpredictable months of the year and heavy thunderstorms were possible at any time. September was the best month as it was dry for one out of four years (1917 was one of those years!) October was usually the wettest month of the year and usually marked the beginning of winter. The weather forecast before the battle opened on July 31st. was that "the weather is likely to improve generally but slowly" but although the average rainfall for the beginning of August was only 8mm. of rain, in fact 76mm. fell over the next 4 days! Whatever else he was, Haig was not a lucky General. 3. The German defences The Germans were well aware of the strategic importance of Flanders and that is why this was the most heavily fortified part of their line. British security was very poor and the Germans knew all about the forthcoming battle and had taken their countermeasures well in advance. It was no coincidence that they four days before the battle was due to begin they had carried out a tactical retreat from their front line back to the Passchendaele ridge. This left a zone of real and potential marshland in the low-lying land between their new front line and the British. Their new positions, the Hindenburg line, were a defence in depth of three lines, the third being beyond the range of the British guns. Between these lines was barbed wire, scattered concrete pillboxes and machine gun nests. The barbed wire funnelled the attackers into killing zones swept by machine guns and carefully registered by the artillery so that the attackers could be annihilated by a crippling concentration of shells. (You can see German Pillboxes at Tyne Cot cemetery even now, the great cross is built over one and the pillbox to the left of the entrance and central pathway was used by stretcher-bearers as their HQ during the assault on Passchendaele Ridge; the one on the right was used as an RAP by the Medical officers. The stretcher bearers had an appalling job in the mud, one stretcher required a minimum of eight bearers because of the terrain and the heavy weight of the wounded man with water and mud soaked clothing and blanket which had to be carried at least a mile in freezing conditions in the rain. The stretcher-bearers suffered a dreadful mortality from shellfire.) (Tyne Cot was so called because British soldiers from the Tyne thought that a barn west of the Broodseinde-Passchendaele Road, looked like a local cottage, or cot.) The Germans had developed a very effective technique of counterattacking as soon as they were driven out of their positions. They held fresh troops in reserve, specifically for the purpose of counterattacking, and these would be able to assault their exhausted enemy who would then be occupying the completely unfamiliar German trenches. German artillery was also better than the British, it had a longer range and was more accurate and with better shells that were more likely to explode! They also had the secret weapon of mustard gas delivered by shellfire. This was a liquid that caused blistering of the skin if touched or if the unfortunate soldier even walked through the zone of evaporation and the effect on the eyes was disastrous. If inhaled, it could cause pulmonary oedema. No antidote was to be found and after its first use in a barrage on July 26th. one man in six out of the 5th. Army who were assembling for the assault became a casualty! The assembling troops and artillery were under direct vision from the high ground of the Ridge and the German shellfire was used with great effect to disrupt Haig's preparations for battle; the effects of high explosive and gas bombardment forced Haig to make two delays from the original start date of the 19th. of July. These effects of the geography and the weather were made many times worse by Haig's insistence on a preliminary bombardment of the German lines, even though he had been warned about this. Many shells fell short and the result was to turn a very difficult battleground into an absolutely impossible one because it created a quagmire of quicksand-like proportions! Nevertheless this preliminary 2 weeks bombardment was so severe that one German division actually deserted its front. Unfortunately the German counter-battery fire was not affected and the Australian artillery suffered greatly as it had to be exposed on the open flats.

The Germans used a mixture of shells; high explosive, mustard gas and "sneezing gas". This latter was to make the gunners sneeze and lacrimate so much that they could not wear their gas masks and they then succumbed to the mustard gas.

The Battle The official name of the battle is 3rd Ypres, but it is universally known as the Battle of Passchendaele because it was really a series of engagements with the one objective of taking Passchendaele Village and its Ridge. It commenced on the 31st of July with an attack on the Northern Flats at Pilcken to the left and the Gheluvelt Ridge to the right. The troops at Pilcken were to be supported by massed tanks and this attack was initially successful but, unfortunately, the right flank was held up and failed to reach its objective of the Gheluvelt Ridge. Then at 4.00 PM the rain started. It lasted for days and of course the flooding made it impossible for the tanks to operate! Although Haig had originally only proposed a short battle to break through the German Lines and this was now patently impossible, he still insisted on continuing the battle at Langemarck to the North. General Gough, whom Haig had chosen because he was the most aggressive of his Generals, actually advised Haig to cease the battle but Haig, inflexible as ever, continued the battle despite horrific losses for another three weeks until August 26th, before he closed it down. He then decided to change the axis of attack from the North to the East and, when finer weather came, to order the assault on the ridge itself. He also changed Generals and General Plumer was put in charge of the next assault. Plumer, one of the most astute of the Generals, was an advocate of a small-scale limited advance under cover of a creeping barrage which would also prevent the German counterattacks. This would lead to a concentration of force on a narrow front, it would be easier to relieve the tired men and food and ammunition could readily be brought up to them. The men were to advance behind the shelter of the exploding shells and be hidden from the enemy by the smoke and dust of the barrage, however this would, of course, be impossible if it rained and the ground turned into liquid mud. The Battle of Menin Road on September 20th was the first of three famous victories using the new tactics. At dawn on that day, after a 5 day bombardment, the Anzacs made a successful attack with two Australian Divisions side by side and supported by a Scottish Division on their left. It was here that 2nd Lt Fred Birks won his posthumous V. C.; he rushed a machine gun post in a pillbox which was holding up the Battalion, killed the enemy and captured the gun, then organised a party to take another strongpoint and captured an officer and 15 men. A shell burst buried several of his men and Birks was attempting to dig them out when he was killed by another shell burst.

The Australians reached the lower part of Polygon Wood and Black Watch corner, this cost them 5000 casualties. They were then relieved, the captured ground was consolidated and a supporting Railway line and plank roads were quickly laid down so that supplies could reach the new front line. On September 26th the weather was still fine and the ground had dried out; on that day Plumer's rolling barrage worked well and the Anzacs were able to advance concealed by a barrage "like a Gippsland Bushfire" as Bean put it. The 4th. Australian Division then took the rest of Polygon Wood, or what was left of it, and the Butte (which was the local Rifle club's Rifle range; on top of the Butte is now the A.I.F. 5th Division memorial). They had thus reached a position where they could strike at the main Broodseinde Ridge. The Battle of Broodseinde took place at dawn on October 3rd. The waiting Australian troops were mortared in their trenches by the enemy and as they went over the top they were surprised to see German troops advancing under cover of the mortar bombardment; by chance the opposing troops had each launched an assault on each other at the same time! The Germans were eventually driven back by the Australian bayonet charge, however a German machine gun was causing casualties and holding up part of the attack. Sergeant Lewis McGee, armed only with a revolver, ran 50 yards across bullet swept ground, shot some of the crew and captured the gun. He reorganised the advance and was awarded the V. C. for his outstanding leadership during the week's fighting; unfortunately he was killed on 12th October without knowing of his award. He is buried in Tyne Cot Cemetery Grave No. XX.D.1. After the bayonet charge, the Germans retreated to their trenches where they, and their reserves, were caught by the British creeping barrage that caused them many casualties. The barrage wandered deep into the German lines and then came back for the Australians who followed and eventually captured the Ridge on October the 4th. When the Australians reached the Ridge, they were able at long last to see the German rear lines stretching before them, the only obstacle to their success was the German occupied Village of Passchendaele to their north. These three smashing victories vindicated General Plumer's step by step technique and were possible only because the weather had been dry enough to allow the quagmire to drain away, but it started to rain again on the 5th., the next day. It was not a shower but a steady soaking downpour. Haig however, encouraged by the three successes, ignored the rain and decided to make a further attempt to break the Germans on the Ridge, even alerting the cavalry to be ready to follow up! He ordered the Anzacs to take Passchendaele on October the 9th even though the wind and rain had now developed into a gale force storm. He appeared to be quite unaware of the appalling conditions on the front or that the wire had not been cut and the Germans had replaced their soldiers with fresh support troops in their relatively dry pillboxes. His reason for persisting was to allow his troops to winter on the ridge, without the Germans overlooking them, and with drier conditions once the front line was out of the swamp.

The Australians attacked and at Augustus Wood, near the Tyne Cot, Captain Clarence Jeffries organised a party and attacked a pillbox, capturing 4 machine guns and 35 prisoners. He led another charge on the next blockhouse when he was killed by machinegun fire. He was awarded the posthumous V. C. and was buried at Tyne Cot, not far from Sergeant McGee (his grave is No. XL.E.1). According to John Laffin, every officer of his Battalion was killed or wounded that day. Incredibly, and mainly because of the valour of Captain Jeffries, 20 men actually reached the rubble that used to be Passchendaele church. Unfortunately the British troops on their right were unable to support them and the Australians were forced to retreat all the way back to the mud holes that had been their front line. By now, their artillery was running out of ammunition and their shells were burying themselves in the liquid mud and expending themselves relatively harmlessly in a cloud of steam and a fountain of water. Yet even now Haig went on with the battle, even though the rain and bitter cold had set in and on October the 12th. this lunatic ordered another attack, which was fated to fail miserably, with men struggling up to their knees and waists in the dreadful stinking mud and with their rifles and machine guns clogged with it. This was when Sgt. McGee was killed. The only solid objects in this endless waste of cratered mud were the German concrete pillboxes with their machine guns which were protected from the mud and which operated only too well. This attack cost 7000 casualties, The Australian 3rd Division lost 3199 lives in the 24 hours of this attack. The exhausted Australians were at last withdrawn but Haig was still pathologically obsessed with capturing Passchendaele Village and ordered the Canadians to take over the battle. However their General Currie, who was one of Haig's Generals who retained his common sense, refused to move until the weather had eased and adequate supplies were available. Eventually, on November the 12th the Canadians took Passchendaele, or what was left of it, and the battle was finally over. Air photographs of Passchendaele were taken after the battle; it is estimated that half a million shell holes could be seen in the half square mile of the picture!. This, presumably, was where Haig expected his troops to winter. And so the British gained their objective, although it was quite useless to them in terms of the original plan; the attack from the sea at Nieuport had been abandoned, and there was no hope of breaking through to the German occupied Channel ports, which were eventually blockaded by hulks sunk at Zeebrugge. Passchendaele cost over half a million lives over its 3 months. The Germans lost about 250,000 lives and the British 300,000 of whom 36,500 were Australian. 90,000 British or Australian bodies were never identified, 42,000 were never recovered; these had been blown to bits or had drowned in the dreadful morass. Many of the drowned were exhausted or wounded men who had slipped or fallen off the duckboards and were unable to escape the filthy, foul-smelling glutinous mud, sinking deeper to their deaths as they struggled. For 76 years, the name of Passchendaele has been synonymous with all that is loathsome in war, it certainly represents the futility and stupidity of warfare. Siegfried Sassoon wrote:

but surely Passchendaele must also epitomize the extraordinary bravery of the fighting soldiers who attempted what was quite obviously impossible but by superhuman efforts of will actually achieved success. That their efforts were squandered by their High Command can in no way minimise their incredible accomplishments. |