|

The Aim

The losses on the

Western Front in the early months of war in 1914 and 1915 were far

higher than each warring nation had anticipated. After early German

advances in Flanders, a virtually stationary Western Front ran from the

English Channel to the Alps and thousands of lives were required for

advances measured in yards. An alternative way of waging war against

Germany and Austria-Hungary seemed highly desirable to the Allies,

especially since it seemed likely that other states would enter the

fray, Greece and Italy to join the Allies and Turkey and Bulgaria the

Central Powers. The 'Young Turk' leaders in Constantinople decided to

ally with Germany. They opened the Dardanelles to German warships, which

bombed Russian Black Sea ports before the formal Turkish declaration of

war. In this context the Dardanelles, or Gallipoli, campaign was

conceived. Its leading advocate, Winston Churchill, then first Lord of

the Admiralty, was convinced that the Dardanelles Straits could be

forced, Constantinople captured, Turkey knocked out of the war, Greece

and Italy encouraged to enter on the Allied side, and aid given to the

hard-pressed Russian and Serbian forces.

|

|

|

|

North Beach Gallipoli 1915 & 2002 |

Formation of ANZAC

Before 1914, all major

political parties in Australia supported military training for young

men. Labor leaders such as Billy Hughes, born in London, and John

Christian Watson, of Scottish descent but born on board ship in

Valparaiso Harbour, Chile, were ardent supporters of the Australian

National Defence League. In his recent Soldier Boy: The True Story of

Jim Martin the Youngest Anzac, Anthony Hill explains how young Jim

was imbued at school with pride in being part of the British Empire and

was keen to join the military training scheme for boys of twelve and

above. Jim enlisted at 14, giving a false age, and had not reached his

fifteenth birthday when he died of typhoid fever in a hospital ship off

Gallipoli in October, 1915.

When war broke out,

the Labor leader, Scotland-born Andrew Fisher, supporting the

England-born Liberal Prime Minister, Joseph Cook, declared that

Australia would stand beside the mother country to help and defend her

"to the last man and the last shilling". About 40 per cent of all

Australian males aged between 18 and 45 voluntarily enlisted to serve in

the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF), that is about 417 000 men, of whom

about 60 000 died in all campaigns and another 160 000 were wounded or

maimed. At least a quarter of the Australian volunteers were born in

Great Britain and Ireland, Robert Rhodes James's estimate being 35 per

cent. About 98 per cent of the rest were of British or Irish origin. The

immigration rate from the United Kingdom was exceptionally high between

1910 and 1914. 'Simpson' - 'the man with the donkey' was John Simpson

Kirkpatrick, a recent Geordie emigrant.

'Rule Britannia',

'Soldiers of the Queen' and 'Sons of the Sea' were sung at recruiting

offices in Adelaide and Sydney, Wellington and Christchurch, as loudly

as in Birmingham or Glasgow. In 1914 and 1915 there was little

difference between the volunteer rate in Australia of Protestants and

Roman Catholics of Irish descent, but the number of Irish volunteers

fell sharply after the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and after Cardinal

Mannix, Archbishop of Melbourne, took a leading part in opposing

conscription in the referenda of 1916 and 1917.

In 1915 almost all

Anzac troops considered themselves part of a wider British people and

wanted to be regarded as British, not only as Australians or New

Zealanders.

|

<< Anzac Cove 1915

When Australian units were photographed in Egypt they

usually chose themselves to wear the standard British pith helmet.

Most

Anzac units landing at Anzac Cove wore British-issue caps, but when

after the war George Lambert was commissioned to paint that scene he was

instructed to show them with slouch hats. |

The Australian forces

soon made themselves distinctive. One example of Australian ingenuity

was Lance-Corporal Beech’s periscope rifle invention which

enabled gunners to fire without putting their heads above the trenches.

Two British generals, Walker and Birdwood, made important contributions

to Anzac successes but their role was played down by Charles Bean and

some other Australian historians in order to elevate the role of Monash,

an excellent planner but an indifferent commander in the field. Birdwood

and Walker tightened discipline among the Australians without alienating

them or reducing their aggressive spirit.

|

|

|

The Anzac piers with The Sphinx

in the background |

Some Australian troops

considered British regiments stuck too much to regulations when

encamped, whereas some British troops thought Australian regiments made

bad conditions worse by lack of attention to routine. Birdwood admitted

to Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, that, although 'my men

are A1 in attack', they are 'curiously callow, and negligent, and the

only thing I fear is a really heavy night attack ... as I cannot get the

men to bestir themselves and hurry up to repulse an attack at once'. The

Australians were usually distinguished by boldness in attack, the

British by discipline in retreat. The New Zealanders were widely

thought, not just by themselves, to possess both Australian and British

virtues in warfare. Perhaps the most remarkable individual achievement

of the campaign was that of Lieutenant-Commander Bemard Freyberg, awarded the

DSO for swimming naked in an ice-cold sea for two miles to light flares

on the coast at Bulair. Freyberg later gained the VC in France and

became Governor-General of New Zealand, among other distinctions. The

epitome of Australian guts was Albert Jacka, who killed seven Turks in a

single engagement and was awarded the VC.

The Naval Campaign

The directive that

'The Admiralty should prepare for a naval expedition in February to

bombard and take the Gallipoli peninsula with Constantinople as its

objective' was later derided by opponents of the plan, but it came close

to success. Reports recovered later from the Turkish staff revealed that

on 19 March nearly all the Turkish ammunition was expended and that 'A

naval attack executed with rapidity and vigour might have been

successful.' The Gallipoli campaign proved more than once that often a

small group, even one person, may make a great difference to mighty

issues. The mines of a single Turkish mine-layer had a powerful effect

on the naval battle, more perhaps than shells from all the Turkish

guns.

British minesweepers,

manned by civilian crews, refused to continue to clear the mines whilst

under Turkish shell-fire, and that proved a crucial failure. After the

sinking of HMS Irresistible and the French ship Bouvet and

severe damage to the French ships Gaulois, Suffren and Charlemagne and

to HMS Inflexible, Agamemnon, Lord Nelson, Albion, Admiral Carden

called off the attempt to enter the Straits. Carden feared that his

ships could not deal with the Turkish guns until the mines were cleared,

but that the mines could not be cleared so long as the Turkish guns were

intact. Under Carden or his replacement, Admiral de Robeck, the Allied

fleets never tried to force an entry into the Sea of Marmara, even when

thousands of troops were fighting on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

When ships' gunners

could get a sight of Turkish positions, they were generally accurate and

effective, with the result that few Turkish officers would risk an

advance across ground vulnerable to their fire. Inevitably, there were

some instances of 'friendly fire', the most devastating being when a New

Zealand battalion close to breaking through the Turkish lines was

shelled from a British warship and forced to retreat to better cover,

but overall the ships ensured that the army's artillery, often seriously

short of ammunition, was able to compete with Turkish fire.

However, a significant

reason for Allied failure during the land fighting of 1915 was poor

co-ordination between the British Army and Royal Navy, although

co-ordination between General Sir Ian Hamilton and his subordinate

military commanders was not much better. Especially weakening was

division at the very head of the Royal Navy. The aged Admiral 'Jackie'

Fisher returned to the Admiralty as First Sea Lord at the invitation of

the responsible minister, Winston Churchill, who believed that Fisher

still had 'fire in his belly'. Fisher initially supported the

Dardanelles concept but soon became its fiercest critic at the very time

strong support was needed for it to have a real chance of success.

Warships were very

vulnerable to submarine attack in 1915, when depth-charges had not yet

been invented. The sinking of HMS Triumph and Majestic by the

German U21 under Lieut. Commander Hersing forced the withdrawal of the

largest British and French battleships from the Eastern Mediterranean,

with demoralising effect on some of the troops. On the other hand The

Australian AE2 torpedoed Turkish gunboats well inside the Narrows before

it was itself destroyed. British submarines under Lieutenant Commanders

Nasmith, Boyle and Stocks did substantial damage to Turkish ships in the

Straits, creating panic in Constantinople.

The Turkish Forces

Few of the Allied

troops had previous experience of modern warfare, but many of the Turks

were battle-hardened. They had not performed with much distinction in

the recent Balkan Wars, but then they had been fighting to retain

provinces with huge non-Turkish majorities. At Gallipoli the Turks felt

they were defending their homeland, especially when they learned that

Constantinople would come under Russian rule after a Turkish defeat.

Allied troops soon realised the stupidity of HQ propaganda about low

Turkish morale and lack of equipment.

Although medical organisation was

even worse on the Turkish than on the Allied side, most Turkish troops

fought with great courage, even when required to attack well-defended

positions without cover, as at the Nek in May and Helles in December,

just before the Allies withdrew from the peninsula. Their successful

defence of their lines at Krithia in May was significant in the final

outcome of the campaign.

|

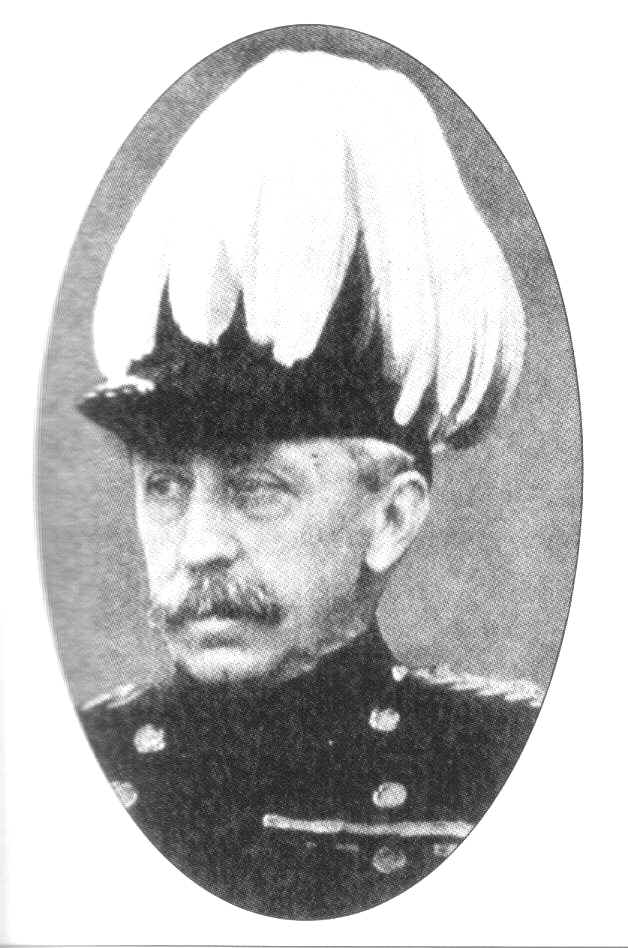

Mustapha Kemal ended

the Gallipoli Campaign as Turkey's greatest war hero, with little

tribute being paid to the able overall strategist, the German General

Liman von Sanders. Kemal was responsible for some of the bloodiest

Turkish losses and, had the Allies prevailed, might well have been

denounced for unnecessary deaths, since the Turks had only to hold on to

their hill positions to win the campaign, whereas the Allies had to

attack in order to justify the entire venture. On the other hand Kemal

rallied his troops successfully when the Anzacs nearly broke through

soon after their first landings and in later crises. |

|

|

Kemel |

von Sanders |

Early in the campaign

many Anzacs believed the Turks practised vile atrocities on prisoners,

but later experience suggested that many disfigured corpses had suffered

from shrapnel rather than bayoneting after capture, although two British

officers were bayoneted in cold blood after surrender at Suvla in

August. After the truce at Lone Pine in May, during which the Turks were

able to pick up their over 10 000 casualties, Turks and Allied troops

regarded each other much more as decent human beings.

However, Turkish

treatment of prisoners of war was worse than treatment by Germans,

French, British or even Russian captors. The chilling account provided

by Greg Kerr in his Lost Anzacs is a salutary corrective to the

Turkish monument at ANZAC Cove, 'depicting a Turkish soldier fondly

cradling a wounded Australian', as Rhodes James put it in his Gallipoli.

Turkish troops were often threatened with immediate execution if

they withdrew and with officers such as Kemal that was no idle threat.

On the Allied side General Hunter-Weston recommended the MC to a young

subaltern who summarily executed three men for alleged cowardice.

Whilst the Gallipoli

campaign was being waged, the ' Young Turks ' government launched an

horrific attack on Armenian civilians, some of whom were suspected of

supporting the Allied cause. The Turkish massacre of the Armenians was

only exceeded during the century by the Nazi holocaust of Jews and the

mass killings ordered by Stalin. Of two million Armenians in Turkey in

1914, Alan Moorehead's estimate was that 'three quarters of a million

were dead or dying by the time the frantic rage of their tormentors had

exhausted itself' by 1916.

The early fighting

The British commanders

in Egypt as well as on the Western Front were reluctant to give the

swift backing to the Gallipoli enterprise essential for maximum chances

of success. There was abysmal lack of co-ordination between the French

and British forces, and between the British naval and military staffs,

although things were little better in this respect between German and

Turkish officers on the other side. One key difference, however, was

that General Sir Ian Hamilton was reluctant to interfere with the

immediate commanders in the field, who in their turn were often

uncertain about his overall strategic intent, whereas von Sanders forced

his decisions on subordinates. Several British officers were brought out

of retirement in 1914: the most able were usually used on the Western

Front and some appointments to commands at Gallipoli, such as Sir John

Stopford, proved disastrous.

|

Some British

operations were carried out skilfully and successfully, such as the

organisation of supplies from Egypt, but there was considerable muddle

and confusion in the landings. Landing gear, medical supplies, water

carriers, and much besides, were all available in the vicinity but

rarely where and when most needed.

A popular joke among the troops

linked Imbros, Mudros and Chaos, the first two being the islands serving

as supply bases. Lines of Communication were weak and there was

resentment among the troops at reports of creature comforts for the HQ

staff at Mudros.

Hamilton was for some weeks mainly on HMS Queen

Elizabeth and in poor contact with shore operations. In the first wave of

landings in April, 1915, British troops under Hunter-Weston were

responsible for landings at Cape Helles, the southern tip of the

Peninsula.

The core was the regular 29th Division, supported by

battalions of recent volunteers. Some landings, such as that at W Beach,

met ferocious Turkish gunfire. |

|

Mule Gully Gallipoli |

As the Lancashire Fusiliers tried to

reach the beach they lost six officers (including the commanding officer

and his next-in-command soon afterwards) and 183 men killed, four

officers and 279 men wounded, and 61 men missing, out of 950 who started

out.

Six VCs, 2 DS0s, 2 MCs and one DCM were awarded at W beach on 25

April. The Dublin Fusiliers, Munster Fusiliers and Hampshire Regiment

suffered heavy losses, too, at V Beach under heavy Turkish fire, many

being killed as they tried to disembark from the River Clyde.

At X beach the Royal

Fusiliers met little Turkish resistance, nor did the South Wales

Borderers at S beach, or the King's Own Scottish Borderers, South Wales

Borderers and Plymouth Battalion of Marines at Y beach. Unfortunately,

Hunter-Weston thought his task was to land the troops successfully and

failed to order immediate progress inland. Thus the Turks had ample

opportunity to reinforce their positions, and the belated Allied

penetration inland was bitterly contested. At 'Y Beach' there was

uncertainly whether Lt-Col Koe of the Scottish Borderers or Lt-Col

Matthews of the Marines was in command, with the result that no one was

effectively in charge. After Koe and many other officers had been

killed, some troops panicked and sought evacuation on the boats, even as

new troops were being landed and the Turks were retreating because of

losses under naval gunfire.

|

The Allied dilemma was

that energetic attack was the only way of securing victory, and assaults

on defended heights immensely bloody, but early aggression might have

ensured that the Turks did not occupy positions from which they later

dealt out severe punishment.

Morale varied greatly from unit to unit.

The Border Regiment broke and ran when charged by the Turks on 28 April,

whereas the Royal Fusiliers and Royal Scots successfully repelled a

similar attack on 1 May.

In June the Manchesters, Lancashire

Territorials and Worcesters broke through nearly to Krithia, which would

have forced a massive Turkish retreat, but Hunter-Weston reinforced the

stationary Royal Naval Division, not the advancing units.

Hunter-Weston.

a martinet who was strangely enough very popular with his men, collapsed

in July, leaving behind an army utterly exhausted and incapable of

further offensive action.

Indian and British losses at Gully Spur on 28

June were even higher than anything at Anzac, but Turkish losses were

higher still and the Turks on Helles were close to breaking point. |

| Gallipoli, Turkey. 1915. Steps cut in the

hillside and strengthened with packing cases behind Pope's Post. (Donor

Captain R.J. Webster) |

The landings at Anzac

Cove in April were a mile north of those intended. Whether strong

currents were to blame, errors by Lieut. Commander Waterlow, the British

naval officer directing the landings, or even a late change of plan by

Generals Birdwood and Throsby, remains uncertain to this date. Yet the

initial landings were successful, since the Turks did not expect them,

and two parties of Australian troops under Captains Lalor and Tullock

fought their way inland. Lalor was a scion of an old English military

family, who had deserted from the Royal Navy, fought in revolutionary

wars in South America and then sailed to Australia to enlist in its

army.

Lalor ordered his men

to dig in on hill Baby 700 but they were reported by a scout sent to

check on their progress to be 'smoking and eating as if on a picnic',

one soon interrupted by a murderous Turkish counter-assault. The

Australians then counter-attacked up the hill against massive odds and

Lalor, wielding an old family sword, was killed with many of his men. An

hour's picnicking exacted a heavy price. Nearly all the Anzac units were

handicapped by razor-sharp cliffs and deep ravines, unsuspected since

they landed at the wrong beaches and had the wrong maps. They also faced

the most able and determined Turkish commander in Kemal.

| The main effort of the

French troops was on the Asian shore of the Dardanelles, where they

captured the fort at Kum Kale previously badly hit by British warships.

Turkish troops who went through the motions of surrendering killed the

French officer accepting the surrender, following which French troops

executed eight Turkish prisoners.

The French commanders had problems

with their Senegalese regiments, which sometimes fought hard and

sometimes surrendered under little pressure. |

|

| Sedd-el-Bahr, Turkey. 1915-05-06. Scene

from the beached ship SS River Clyde showing British Army troops landing

at V Beach across a path of barges and pontoons from the ship. This

landing led to an Allied drive up the end of the Gallipoli Peninsula. |

Hamilton had great

difficulty in preventing the French commander, General D'Amade, from

ordering total evacuation. Some of the French generals, such as General

Bailoud, proved very inadequate, but great courage was shown by most of

the French forces. At Helles their attack on Kereves Spur, heroic but

unavailing, greatly impressed allies and enemies.

The heavy Anzac losses

led the Divisional Commanders, Major-General Godley of the New

Zealanders and Scottish emigrant Major General Bridges of the

Australians, to recommend that Anzac Beach be evacuated. Hamilton

instead urged them to dig in, which they did and so ensured that the

campaign became immortalised in Australian and New Zealand history. The

Australian approach was embodied in Colonel Braund, whose defence of

Russell's Top, overlooking the main landings, probably saved the

situation. Braund was accused by New Zealand Colonel Malone of having

'no defensive position, no plan, nothing but a murderous notion that the

only thing to do was to plunge troops out of the neck of the ridge into

the jungle beyond'.

Braund was soon

afterwards shot by an Anzac sentry whose challenge he did not hear.

Malone nearly shared the same fate and several Allied troops died in

that way. Within a week of the landings the Anzacs suffered 6,554

casualties, including 1,252 dead. The opposing Turks, so their own

officers estimated, suffered 14,000 casualties, the majority killed.

British Marine reinforcements sent to support the Anzacs were described

by General Birdwood on their arrival as 'nearly useless ... special

children of Winston Churchill, immature boys with no proper training',

but they proved him wrong and won Anzac respect by scaling and

re-capturing Dead Man's Ridge on the night of 2-3 May after the

Australians had been forced to retreat.

Within a few days of

the Anzac Cove landings, the situation there was relatively quiet, so

that Hamilton moved some ANZAC troops south to join in what he hoped

would be a critical attack, The Australians lost over a thousand men

during an advance of under 600 yards up the steep Krithia Spur on 8 May

when their courage made them deeply admired among the Allied troops who

had not been at their side at Anzac Cove.

Quite apart from

bullets and shells, lice and flies, together with poor food and water

shortages, contributed to acute dysentery - the Gallipoli Trots, which

affected three out of four Allied troops. Dental disease also became

acute. Australians suffered severely from these scourges, partly because

they were generally less rigorous in hygiene routine than the British or

New Zealanders and partly because they bathed frequently in the

contaminated sea. The British, held by the Australians to keep their

towels dry, may have benefited for once from aversion to water. On the

positive side, British aircraft under Commander Samson, whilst not

inflicting a great deal of actual damage, were feared by the Turks and

greatly encouraged the Allied troops.

|

Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey. c. 25 July

1915.

This photograph depicts one of the many difficulties

with which our troops were confronted on Gallipoli. Before bringing in

troops for the big battle of August, it was necessary to provide stores

of water. |

| The great platform leveled

for water tanks above Anzac Cove are seen here, and troops are dragging

the water tanks

up the hill to get them into position. |

The later fighting

The best Allied

military plan at Gallipoli was devised by Lt-Col Skeen, a scholarly

Scottish migrant who lectured at Quetta Staff College before the war. It

revolved on the capture of Sari Bair Ridge and Chanuk Bair, the heart of

the Turkish position. The plan was partially adopted by Hamilton in

August: Australians under Walker were to attack the Turkish lines at

Lone Pine, whilst the New Zealanders tried to outflank the Turks to the

north. At the same time, British and French troops further south at

Helles were to attack once more the strong Turkish positions at Krithia

and Achi Baba, and other British troops were to land at Suvla Bay north

of Anzac Cove.

Execution of the plan

was delayed, partly because of the worst accident in the history of

railways in Britain, when at Gretna Green on their way south 210

officers and men of the Royal Scots were killed and 224 injured. The

attempted break-out from Anzac Cove was planned well, but aerial

photographs proved very misleading, since they failed to show a timber

cover protecting the Turkish trenches or a steep gully interrupting any

advance. In bloody and confused fighting Turks sometimes killed Turks

and Australians killed Australians.

The Australians came

close to a complete breakthrough but were finally overwhelmed with the

loss of over 2000 men, the Turks suffering 7000 casualties, in the

bloodiest single encounter during the whole campaign. The New

Zealanders, Wellington Mounted Rifles and the Auckland Regiment,

supported by Gurkhas, Wiltshires and South Wales Borderers, made rapid

early progress towards the key point of Sari Bair. Much of their good

work was undone by the New Zealand commander, Brig-General Johnson, who

ordered a halt until the Canterbury Battalion, which had lost its way,

arrived. The New Zealanders' best scout, Major Overton, was killed

during the advance.

The Gurkhas broke

through their opposing positions and the Turks were nearly encircled,

but Johnson's lack of determination gave the Turks time to reinforce

their positions. Johnson's failure was costly for the Australian 3rd

Light Horse, who had to charge the Turkish trenches at The Nek.

Furthermore, the Welch Fusiliers, protecting the Light Horse flank, were

forced by Turkish bombs back down the hill they were trying to climb.

The Light Horse lost 372 out of 600 officers and men from Turkish fire

within minutes.

The New Zealanders,

Welsh Fusiliers and Gloucesters fared no better: only 70 out of 760 New

Zealanders survived unwounded, the 8th Welsh Fusiliers lost 17 officers

and 400 men, and the 7th Gloucesters lost every officer and sergeant and

over 350 other men. The Turks, too, suffered heavily in these battles,

but Kemal threw all his reserves into the biggest assault of the

campaign on 10 August at Chanuk Bair and The Pinnacle against the Allied

front trenches in the Anzac section. None of the British troops, mainly

Wiltshires, survived the assault.

The British, French

and Indian troops at Helles did their part in the August plan, but lost

heavily in assaults on strong Turkish positions. The key weakness was

the Suvla Bay landings. Blame lies mainly on Hamilton, who surrounded

his plans in an air of secrecy: Turkish spies knew more of his plans

than did his own commanders in the field, let alone his junior

officers.

|

Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stopford: his generalship at Suvla was disastrous and he became the scapegoat for the failure of the August offensive.

He was elderly beyond his years and had never commanded men in battle before.

His specialty was ceremonial duties. His Who's Who entry for 1920 did not mention his time as a corps commander at Gallipoli. In his mind it never happened. |

Hamilton fatally

changed the initial instructions to Stopford to read: 'your primary

objective will be to secure Suvla Bay as a base for all the forces

operating in the northern zone .... If it is possible, without prejudice

to the attainment of your primary objective, to gain possession of these

hills at an early period of your attack, it will greatly facilitate the

capture and retention of Hill 305'. The original plan was justified if

surprise was achieved and rapid advance took place to occupy the ridges

overlooking the bay, but Stopford felt he had done great deeds if his

forces simply managed a successful landing.

Many of the British

troops landed on August 6 at Suvla Bay were inexperienced and had never

undertaken a night landing before. Many suffered severe reactions after

cholera inoculations. Some landings took place significant distances

from the intended points, so that the troops were faced with landmarks

they did not recognise.

One battalion of the

Lancashire Fusiliers lost 60 per cent of its officers and 20 per cent of

its rank and file between the night landing and the following noon.

However, at other landing points there was little resistance and 20 000

men were put safely ashore. Had they advanced resolutely inland, they

might have captured with relatively few casualties the positions at.

Kiretch Tepe and Tekke Tepe. Instead for a day and a half several units

loafed around the beach waiting for instructions and unaware that the

heavy fighting a few miles to the south could only succeed if they

attacked the Turkish positions quickly and vigorously. An East Yorkshire

officer and signaller climbed to the top of Tekke Topi and reported it

unoccupied, but the message never reached Hamilton or any senior

commanders.

The troops at Suvla

Bay were short of water and were soon blisteringly hot, but staying on

the beaches did not help them or the other Allied forces. The positions

they should have attacked were soon occupied by Turkish gunners who

rained down fire on the Suvla beaches. The East Yorkshires were shot to

pieces from heights they themselves could well have occupied. A few days

later, Hamilton and General de Lisle, who replaced the demoralised

Stopford, decided on a further major attack at Suvla across the Salt

Lake which forced the Turks to bring in their last reserves, but British

losses were over 5000 and no significant advance was made. The last

realistic chance to occupy the Gallipoli Peninsula was gone.

The Withdrawal

Hamilton's

replacement, Sir Charles Monro, did not take long to decide that the

Gallipoli positions could not be held, let alone extended to threaten

the Straits and Constantinople, without massive injections of men,

artillery and ships which were not going to be made available. Unfairly

blamed by Churchill for limp capitulation, Monro took the decision which

enabled the remaining Allied troops to fight another day, which many did

on the Western Front and Middle East.

As winter set in,

instead of flies and sunstroke, the troops suffered from frostbite and

extreme cold. At Suvla there were over 12 000 cases of frostbite and

exposure, nearly 3000 at Anzac Cove and 1000 at Helles. One junior

officer found 30 Worcesters frozen to death in a single trench. Heavy

seas made supplies harder to land and any withdrawal more difficult week

by week. Those for staying on argued that bad conditions at sea meant

that losses in trying to withdraw might well be as high as a third of

the troops. In the event, the withdrawal from Gallipoli was perhaps the

most successful part of the expedition.

Monro ordered

withdrawal first from the Suvla and Anzac positions, both of which were

under heavy Turkish counter-attack. Between 14 and 18 December 80 000

men, together with most of their guns and stores, were shipped out

without the Turks being aware that a withdrawal was taking place. The

Helles withdrawal took place only after one of the most ferocious

Turkish assaults of the campaign. Von Sanders did not want the Allied

troops to escape without loss as at Anzac and Suvla, but his assault

against the British 13th Division holding Gully Spur was met with

tremendous resistance: the Turkish losses were never revealed. 164

British casualties were the price of ensuring the complete withdrawal of

over 35 000 men from Helles. Nearly 4 000 horses and mules were shipped

out as well. The French battleship Suffren managed to sink a large

Allied transport ship, but fortunately before it had been filled with

departing soldiers.

Can Gallipoli be

Justified?

The Turkish command

was lax in record keeping and the official Turkish figures of 86 692

killed and 164 617 wounded or missing are likely to be a significant

under-estimate. Rhodes James suggested that Turkish total losses were

about 300 000. Estimates of the British and Dominion losses lie between

198 000 and 215 000, with something like 46 000 dead. Hell's

Foundation by Geoffrey Moorhouse, describes most movingly the

effects of the campaign on Bury, the depot town of the Lancashire

Fusiliers.

Losses in Kitchener's

'New Army' affected particular towns very badly, since many workmates

and school friends enlisted together in 'pals' or 'chums' units and

often died together as well. The Australian dead were about 7,600 and

the wounded and missing about 18,500, the New Zealanders about 2,450

dead and 5,150 dead and missing. French casualties were probably about

50,000. These were dreadful losses compared with British campaigns

during the previous century, although relatively light compared with the

slaughter on the western and eastern fronts in Europe.

The British Royal

Commissions which reported in 1917 and 1918 described the operations as

ill-conceived and ineptly executed, with thousands of lives needlessly

squandered. This view was held, too, by A. P. Herbert, General Sir

William Robertson and, in Australia, Charles Bean. Churchill led

opposition to this view, especially in The World Crisis, and

other efforts to rehabilitate Gallipoli were made by Hamilton, Admiral

Roger Keyes, John Masefield and Ernest Raymond. Their view gained some

backing when it became known that at two or three times in the early

exchanges, the Turkish forces were close to retreat and defeat.

'Optimists' still hold that with more energy in mine-sweeping the Allied

fleet could have passed into the Sea of Marmara before the landings took

place. 'History' seldom makes a final decision on such matters.

Alan Moorehead,

referring to the 'constantly repeated belief that posterity would never

forget' exploits such as those at Gallipoli, asked in 1956, 'who in this

generation has ever heard of Lancashire Landing or the third battle of

Krithia? He answered, 'Even as names they have almost vanished out of

memory'. Now the 'almost' can be omitted so far as the Tommies and

French and Indian troops are concerned. Perhaps because Australia and

New Zealand have less of a burden of history to carry, Gallipoli is

still remembered in the Antipodes.

Propaganda

Distorted propaganda

is usually at its height during wars but corrected in later years. In

the case of Gallipoli the opposite occurred. The official Australian war

historian, Charles Bean, was reluctant to hint that Australians were

ever less than heroic, and in the interests of maintaining good

relationships with Australia, Cecil Aspinall-Oglander, the official

British war historian, toned down even implied criticisms of any

Australian action. As Rhodes James observed, the result of massaging the

truth was an 'Australian mythology that Gallipoli was an Australian

triumph thrown away by incompetent British commanders'.

-

Far worse distortions

disfigure the Peter Weir film Gallipoli, which seeks to contrast

cowardly and idle British troops with ANZAC heroes. Some British troops

did bathe and drink tea at Suvla Bay whilst horrific fighting was taking

place a few miles to the south, but others were as fully engaged in that

conflict as New Zealanders and Australians.

-

Rhodes James noted that the

'suicidal assault' of the Australian Light Horse at The Nek on 7 August

1915 'had nothing to do with the British landing at Suvla, but was

intended to help the New Zealanders, as the film's military advisers

knew'.

-

However, 'the principal Australian sponsor of the film

(Rupert Murdoch) wanted an

anti-British ending, and got it', with 'the deliberately inaccurate

final scenes' of the film, a potent source of Australian republican

sentiments.

-

Few Australians realise that 'the British, French and Indian

causalities were far greater than those of the Anzacs, and that the

British bore the brunt of the fighting - and the losses.'

Far from covering up

British errors, British historians exposed them at every level, from

Kitchener, Churchill, Fisher and Hamilton down. The indecisiveness of

the naval commanders , the muddle at Imbros, the incapacity of Sir

Frederick Stopford, and every other British failing, were laid bare to

the world. This is as it should be, if anyone is to benefit from past

errors, but in 2001 British people, no more or less than Australians and

New Zealanders, can take pride in heroic deeds at Gallipoli, as indeed

can French, Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi people. We should not

allow latter-day propagandists to sow seeds of unwarranted resentment

between peoples whose ancestors fought with great courage in a common

cause.  |