|

Senior

General Vo Nguyen Giap

Senior

General Vo Nguyen Giap was, and is, the only PAVN figure known at all

well outside of Vietnam, the only PAVN general mentioned in most counts

of the Vietnam war, and the only Vietnamese communist military leader

about whom a full length biography has been written.

The disparity

between General Giap and the others-the lone figure standing in the

forefront of a legion of shadowy Vietnamese communist generals-assures

him a prominent place in Vietnam's history. |

But history's judgment on

him, as general, is yet to be rendered.

The three horses pulling the chariot of war are leadership, organization

and strategy. The ideal general in any army would posses to perfection

each of these in careful combination. Evaluating the performance of

General Giap, therefore, must be in terms of his performance as leader,

organizer and strategist, all three. While the jury is still

deliberating, this much about him seems reasonably clear: he was a

competent commander of men but not a brilliant one; he was a first rate

military organizer once the innovative conceptual work was past, a good

builder and administrator of the military apparat after the grand scheme

had been devised; as a strategist he was at best a gifted amateur.

|

Giap of course, is a legend, with a larger-than-life image which the

party and State in Hanoi, as well as the world's press, have

enthusiastically contributed. His metaphoric appellation is Nui Lua,

roughly "volcano beneath the snow" meaning a cold exterior but

boiling within, an apt description of his personality according to those

who know him.

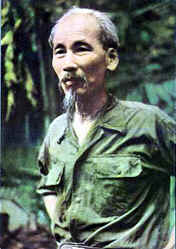

<<

Giap when he started the

first Platoon of the North Vietnamese Army with 344 men in 1944.

Associates also have described him as forceful, arrogant,

impatient and dogmatic. At least in earlier years, he was ruthlessly

ambitious and extraordinarily energetic, with a touch of vanity

suggesting to interviewers that he should be considered an Asian

Napoleon. He is said to be fiercely loyal to those of his political

faction who grant him unreserved loyalty. |

He once told an associate that

he took a "Darwinian view" of politics, and is said always to

have been indifferent to arguments or reasoning based mainly on dogma. He always has been surrounded by political enemies and the victim of

decades of sly whispers campaigns so common in Vietnam. (A typical

whisper: General Dung, not Giap, planned the final successful at the

battle of Dien Bien Phu because Giap had been struck down by diarrhoea.)

Vo Nguyen Giap was born, by his account, in 1912 in the village of An Xa,

Quang Binh province, although other reports say he was born into a

peasant family, but former associates say his family was impoverished

mandarin of lower rank. His father worked the land, rented out land to neighbours, and was not poor. More important as a social indicator in

Vietnam, his father was literate and familiar with the Confucian

classics. Giap, in manner and in his writings, demonstrated a strong

Confucian background. At 14, Giap became a messenger for the Haiphong

Power Company and shortly thereafter joined the Tan Viet Cach Mang Dang,

a romantically-styled revolutionary youth group. Two years later he

entered Quoc Hoc, a French-run lycee in Hue, from which two years later,

according to his account, he was expelled for continued Tan Viet

movement activities. In 1933, at the age of twenty-one, Giap enrolled in

Hanoi University. He studied for three years and was awarded a degree

falling between a bachelor and master of arts (doctorates were not

awarded in Vietnam, only in France). Had he completed a fourth year he

automatically would have been named a district governor upon graduation,

but he failed his fourth year entrance examination.

While in Hanoi University, Giap met one Dang Xuan Khu, later known as

Trung Chinh, destined to become Vietnamese communism's chief ideologue,

who converted him to communism. During this same period Giap came to

know another young Vietnamese who would be touched by destiny, Ngo Dinh

Diem. Giap, then still something of a Fabian socialist, and Diem, who

might be described as a right wing nationalist revolutionary, spend

evenings together trying to proselytise each other.

While studying law at the University, Giap supported himself by teaching

history at the Thanh Long High School, operated by Huynh Thuc Khang,

another major figure in Vietnamese affairs. Former students say Giap

loved to diagram on the blackboard the many military campaigns of

Napoleon, and that he portrayed Napoleon in highly revolutionary terms.

In 1939, he published his first book, co-authored with Trung Chinh

titled The Peasant Question, which argued not very originally that a

communist revolution could be peasant-based as well as proletarian-based. In

September 1939, with the French crackdown on communist, Giap fled to

China where he met Ho Chi Minh for the first time; he was with Ho at the

Chingsi (China) Conference in May 1941, when the Viet Minh was formed.

At the end of 1941 Giap found himself back in Vietnam, in the mountains,

with orders to begin organizational and intelligence work among the

Montagnards. Working with a local bandit named Chu Van Tan, Giap spent

World War II running a network of agents throughout northern Vietnam.

The information collected, mostly about the Japanese in Indochina, went

to the Chinese Nationalist in exchange for military and financial

assistance which in turn, supported communist organization building.

Giap had little military prowess at his command, however, and used what

he did have to systematically liquidate rice landlords who opposed the

communist.

On December 22, 1944, after about two years of recruiting, training and

military experimenting, Giap fielded the first of his armed propaganda

teams, and forerunner of PAVN. By mid-1945 he had some 10,000 men, if

not soldiers, at his command.

During these early years, Giap led Party efforts at organization busting

which, with the connivance of the French, emasculated competing

non-communist nationalist organizations, killing perhaps some 10,00

individuals (although these figures come from surviving nationalist and

may be exaggerated). One of the liquidation techniques used by Giap's

men was to tie victims together in batches, like cordwood, and toss them

into the Red River, the victims thus drowning while floating out to sea

a method referred to as "crab fishing." Giap's purge also

extended to the newly created Viet Minh government: of the 360 original

National Assembly members elected in 1946, only 291 actually took their

seats, of whom only 37 were official opposition and only 20 of these

were left at the end of the first session. Giap arrested some 200 during

the session, some of whom were shot. He also ordered the execution of

the famed and highly popular South Vietnamese Viet Minh leader, Nguyen

Binh. Giap sent Binh into an ambush and he died with a personal letter

from Giap in his pocket. He also was carrying a diary which made it

clear he knew of Giap's duplicity, but Binh went to his death in much

the same manner in which the old Bolshevik, Rubashov, in darkness at

Noon. Giap later confessed to a friend, "I was forced to sacrifice

Nguyen Binh."

With the Viet Minh war Giap faced his most challenging task, converting

peasants cum guerrillas into fully trained soldiers through a

combination of military training and political indoctrination. He built

an effective army. Colonial powers always controlled the colonial

countryside with only token military forces; they controlled the

peasants because the peasants permitted themselves to be controlled.

Giap built an army that changed that in Indochina.

In military operations in both the Viet Minh and Vietnam Wars, Giap was

cautious and so meticulous in planning that operations frequently were

delayed because either they or the moment was premature. Giap's caution

and policies led his opponents to underestimate both his military

strength and his tactical skill. Although as someone noted, in war

everyone habitually underestimates everyone else. Historians,

particularly French historians, tend to case Giap in larger than life

terms; they write of his flashing brilliance as a strategic and tactical

military genius. But there is little objective proof of this. Perhaps

the French write him large as a slave for bruised French ego. Giap's

victories have been due less to brilliant or even incisive thinking than

to energy, audacity and meticulous planning. And his defeats clearly are

due to serious shortcomings as a military commander: a tendency to hold

on too long, to refuse to break victory to intoxicate and lead to the to

the taking of excessive and even insane chances in trying to strike a

bold second blow; a preoccupation, while fighting the "people's

war," with real estate, attempting to sweep the enemy out of an

area that may or may not be militarily important.

Giap always was at his best when he was moving men and supplies around a

battlefield, far faster than his foes had any right to expect. He did

this against the French in 1951, infiltrating an entire army through

their lines in the Red River Delta, and again in advance of the Tet

offensive in 1968 when he positioned thousands of men and tons of

supplies for a simultaneous attack on thirty-five major South Vietnamese

population centres. If Giap is a genius as a general at all, he is, as

the late Bernard Fall put it, a logistic genius. General Giap's

strategic thinking early in the Vietnam War, from 1959 until at least

1966, was to let the NLF and PLAF do it by the Viet Minh War book.

Cadres and battle plans in the form of textbooks were sent down the Ho

Chi Minh Trail. Southern elements were instructed in the proper

mobilization and motivation techniques, cantered on the orthodox dau

tranh strategy that had worked with the French and in which Giap had

full faith. Certain adjustments might be necessary with respect to

political dau tranh and some minor adaptations of armed dau tranh might

be required, his writings at this time indicated but essentially the

necessary doctrine was in existence and was in place.

What changed Giap's thinking, and his assumption that the war against

the Americans could be a continuation of the war against the French, was

the battle of Ia Drang Valley, the first truly important battle of the

war. Giap's troops veterans of Dien Bien Phu, when thrown against green

First Cavalry Division soldiers, experienced for the first time the full

meaning of American-style conduct of war: the helicopters, the

lightweight bullet, sophisticated communications, computerized military

planning, an army that moved mostly vertically and hardly ever walked.

Technology had revolutionized warfare, Giap acknowledged in Big Victory,

Great Task, a book written to outline his strategic response to the U.S.

intervention. The answer he said, was to match the American advantage in

mass and movement or, where not possible, to shunt it aside. He was

still searching for the winning formula when suddenly he was handed

victory. The South Vietnamese Army which had stood and fought under far

worse conditions in January 1975, under minor military pressure, began

to collapse. Soon in could not fight coherently. Giap was handed a

victory he neither expected at the time nor deserved. How much command

responsibility Giap had in the last days of the war, in 1975, is debated

- much direction had passed to General Dung but is unimportant in terms

of distributing laurels, since none was deserved by any PAVN general.

After the Vietnam War General Giap slowly began to fade the scene,

withdrawing gradually from day-to-day command of PAVN. General Dung

began to take up the reins of authority. Giap was given a series of

relatively important short term task force assignments. He supervised the

initial assumption by PAVN of various production and other post-war economic duties. He reorganized and downgraded the PAVN

political commissar system, as the battle organized Reds and Experts tilted ever

more clearly towards the latter. He defended PAVN's budget against the

sniping attack of cadres in the economic sector.

When the 'Pol Pot problem" developed truly serious dimensions in

late 1977, Giap returned to the scene. He spent most of 1978 organizing

an NLF style response for Kampuchea, that in creation of a Liberation

Army, a Liberated Area, a radio Liberation, and a standby Provisional

Revolutionary Government. This was the tried method, but by its nature,

slow. Apparently the politburo judged it did not have time for

protracted conflict, and so in 1978 opted in favour of a Soviet-style

solution: tanks across the border, invasion and occupation of Kampuchea.

Giap opposed it, although evidence of this is mostly inferential,

holding that a quick military solution was not possible, that Pol Pot

would embrace a dau tranh strategy against PAVN and the result would be

a bogged down war. Giap proved to be painfully correct and, for the sin

of being right when all others are wrong in a collective leadership

decision-making process, was eased out of Politburo level politics.

Apparently all factions ganged up on him, but his removal was designed

to eliminate Giap as factional infighting without tarnishing Giap the

legend. It appears he did not resist this power play as he might have

done, with possibly bloody consequences, which may be a tribute to his

better judgements.

Today Giap still is on the Vietnamese scene, but plays a lesser role. He

has taken upon himself the task of lifting Vietnam by its technological

boot straps, has become the leading figure in the drive to raise the

country's technical and scientific capability. This requires, among

other things, soliciting continued Soviet assistance, something Giap is

able to do well because of the regard for him in the USSR. He confers

frequently with Soviet advisors in Hanoi and in the Soviet Union; in

1980 he went to Moscow three times in a nine-month period.

General Giap has been a prolific writer and he continues to publish

although Big Victory, Great Task is more innovative and original. His

most interesting book is Dien Bien Phu, while his worst certainly is

Once Again We Will Win, his initial assessment of what was required to

defeat the Americans which is virtually devoid of correct factual and

technical judgments |